|

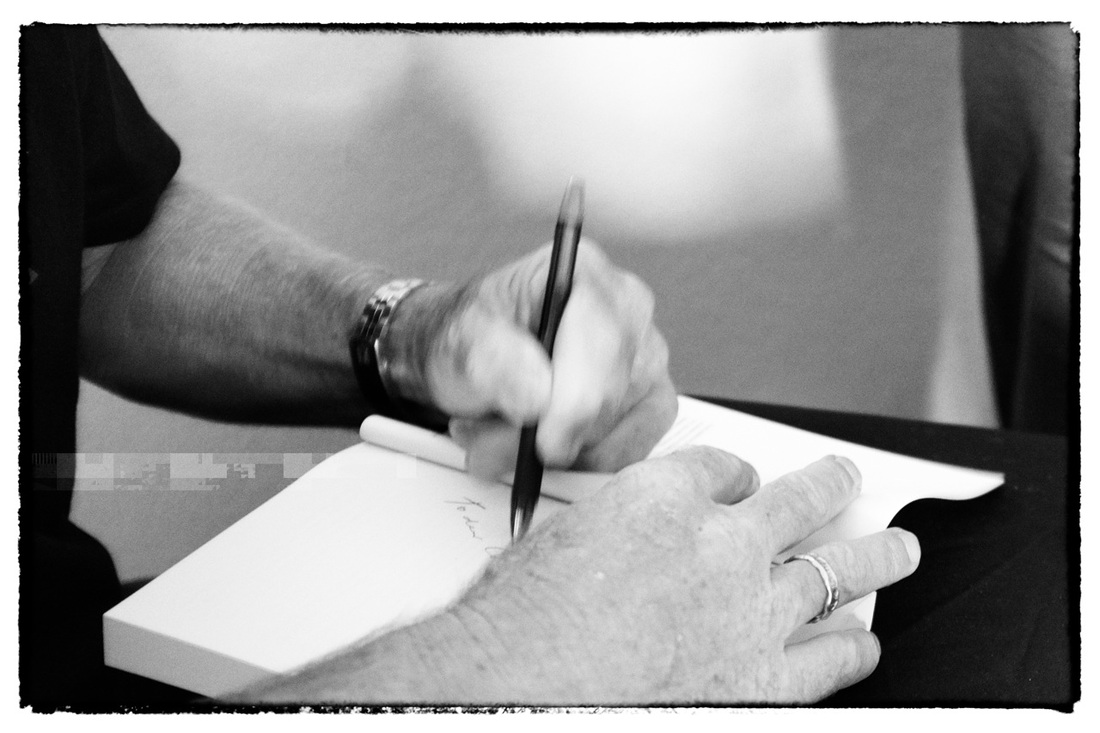

Return Ticket - Jon Doust, published by Fremantle Press